February 5, 2025

1. Introduction

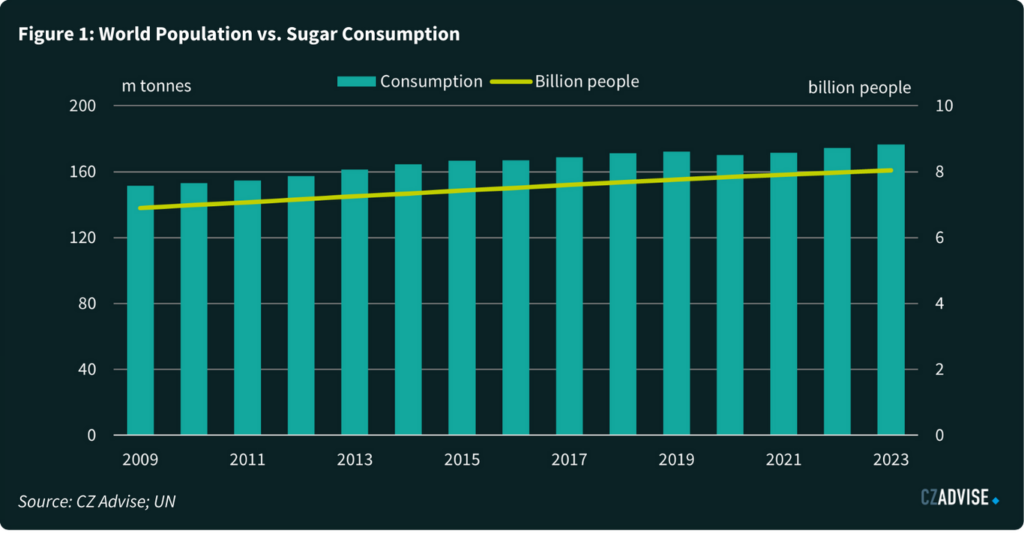

For decades, global sugar consumption has only risen.

Its growth has been propelled by the vast increase in the world’s population and increasing wealth/urbanization, which favours packaged food consumption. This growth story could be about to change.

GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs like Ozempic and Mounjaro are a major breakthrough in obesity (and possibly addiction) treatment and have rapidly become mainstream in the early 2020s. They reduce sensations of hunger, but also seem to reduce impulsive human behaviour like binge-eating calorie dense foods.

As these drug costs reduce and availability increases, they could undermine sugar’s long growth story. This could have a profound effect on the world’s sugar producers and food & beverage manufacturers.

In this paper we will explore the current state of play, suggest a possible future path for global sugar consumption and highlight ways companies can adapt so they can benefit from GLP-1 receptor agonists’ disruption.

2. GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Basics: What You Need to Know

GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs were originally developed to treat type-2 diabetes. When a recently-eaten meal reaches cells in the intestine, they release a glucagon-like peptide 1, or GLP-1. This is one of many hormones that tells the body it should respond to food. Many organs have GLP-1 receptors and when GLP-1 is released they respond by starting digestion. For example, GLP-1 triggers the pancreas to release more insulin.

GLP-1 receptor agonists can perform a similar role, stimulating these receptors to induce desired responses. But much in the same way that Viagra was originally developed to treat hypertension and its more famous use was discovered during clinical trials, researchers noticed that GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs had a host of other benefits apart from helping diabetic patients with insulin response.

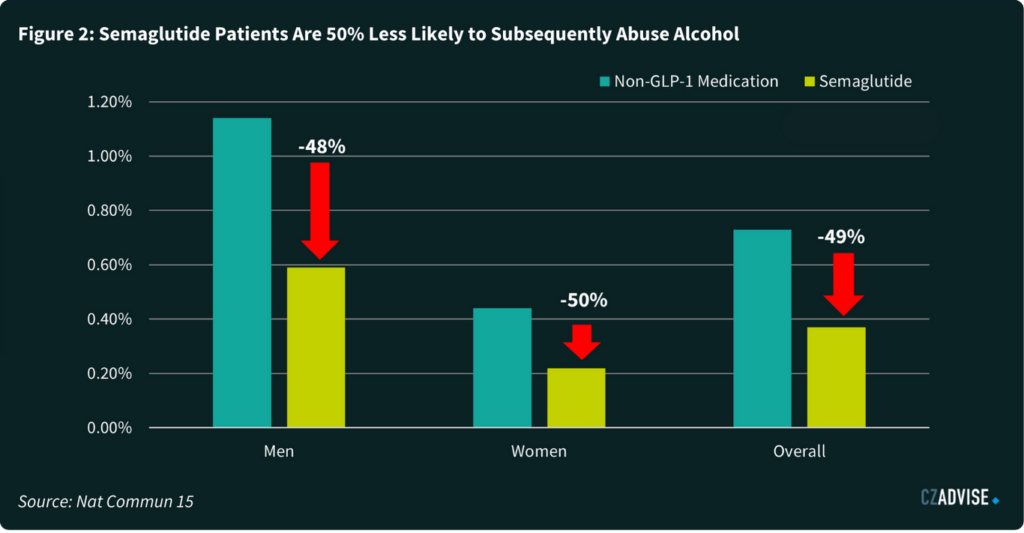

For example, these drugs seem to reduce cravings and impulsive behaviour and so can reduce alcohol abuse, cigarette smoking, and binge-eating calorie-dense foods. One of the first signs of this was the weight loss reported by patients using GLP-1 drugs for their diabetes.

It seems likely that GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs’ effects on the body are rather short-lived and not terribly important for weight loss. It’s possible that they work more effectively in the brain (which in itself would be remarkable because it implies a fairly large molecule can somehow cross the blood-brain barrier). GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs seem to activate neurons which reduce the sensation of hunger and also activate neurons which dampen cravings for food reward. In other words, all of those hyperpalatable comfort foods that people crave when stressed or tired or sad become less appealing.

GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs are now being explored for a range of pathologies. For example, one study showed people on Ozempic are 30% less likely to become addicted to nicotine1. Another study showed GLP-1 drugs reduce the onset of subsequent alcohol use disorder by around 50%2. These are changes on a scale that existing policy measures such as high taxation have failed to deliver.

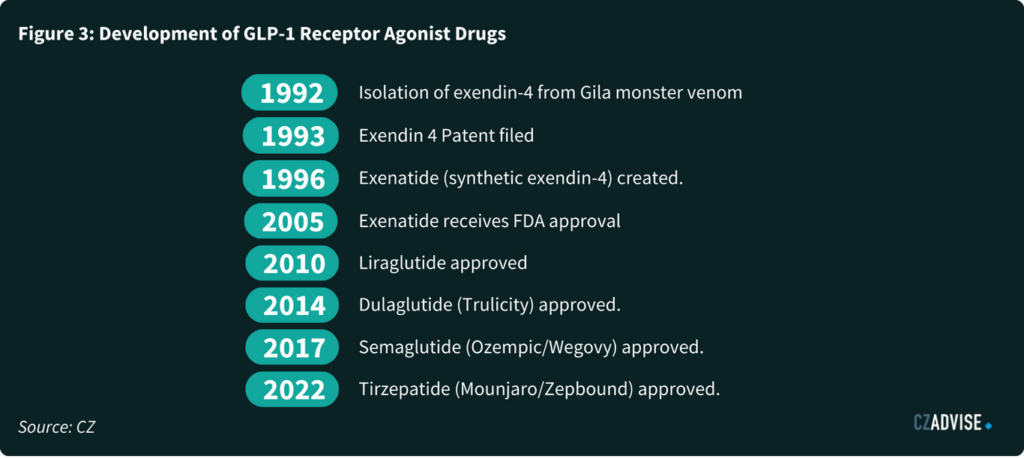

GLP-1 receptor agonists are not new drugs. The original GLP-1 receptor agonist was exenatide, which itself was a synthetic version of exendin-4. Exendin-4 was first isolated in 1992, while exenatide was first synthesised in 1996. However, strange as it may seem knowing what we know now, commercialisation was slow. The US Food and Drug Administration only approved exenatide to treat type-2 diabetes in 2005.

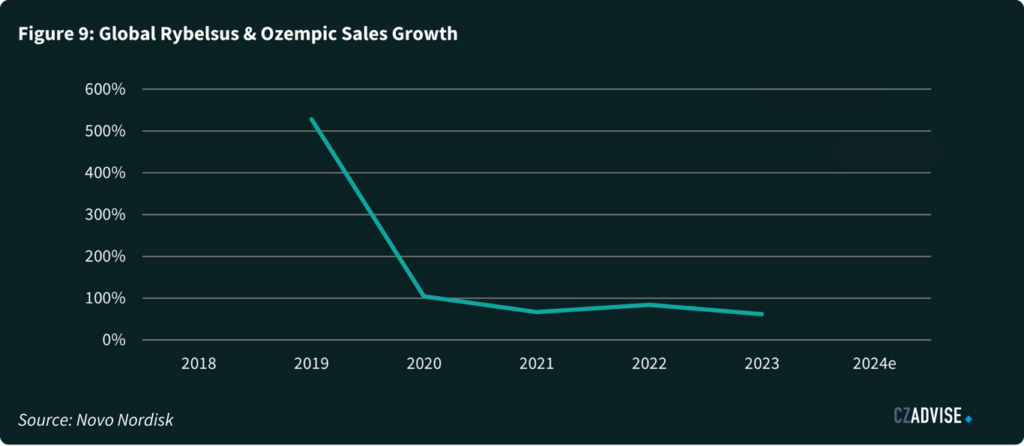

It’s only in the past few years that this class of drugs has really become famous, a word we don’t use lightly. For this, we need to look at Ozempic, which was approved for type 2-diabetes in 2017. This remains its primary use, but it became increasingly common for doctors to prescribe it to obese patients “off-label” as a treatment to control weight.

The GLP-1 in Ozempic is called semaglutide, and given its off-label popularity, drug manufacturers have now re-dosed semaglutide specifically for weight loss. These re-dosed drugs are sold under the brand name Wegovy. Further competition comes from tirzepatide, approved by the FDA in 2022 and now sold under the Mounjaro/Zepbound brand name.

GLP-1 drugs have a long track record of use and are thought to be generally safe, though like all drugs they can have side-effects. However, it’s still not clear if patients are able to keep weight off after discontinuation. This is difficult with food, since unlike other substances it’s essential for human health. It’s not possible to abstain indefinitely, unlike cigarettes and alcohol. But this is also true of exercise and diet. Those who stop exercising are also at risk of regaining lost weight. The body doesn’t give up its energy stores easily.

3. Addressable Market Size and Barriers to Uptake

GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs are likely to completely reshape the global sugar market. They’ve gone mainstream and their addressable markets are huge.

A recent study found that one in eight Americans have tried them3, and 5% of the population are on them at any given time. The 5% figure isn’t static, it’s dynamic as people come off and go back onto the drugs, a bit like yo-yo dieting.

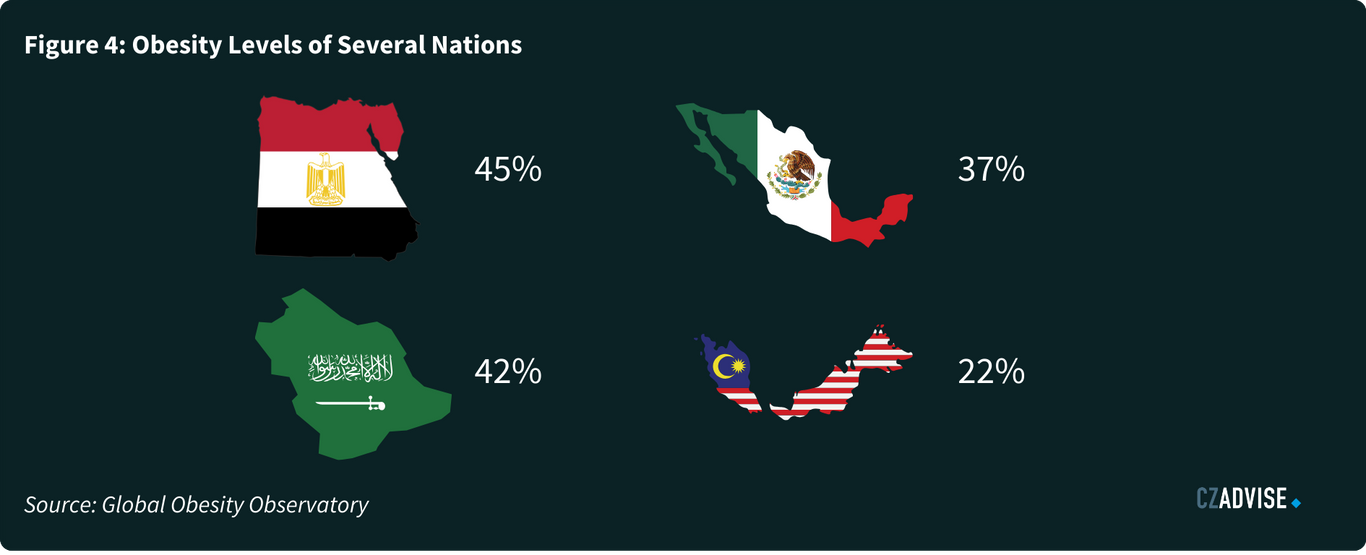

While 5% is an appreciable proportion of the population, it’s a fraction of the total possible market. Measuring obesity is difficult. Body Mass Index (BMI) is a crude measure which doesn’t account for muscle mass. Plenty of people with high BMIs are also healthy. But if we accept BMI at face value, the statistics show that perhaps 1 billion people around the world are obese (by which we mean a BMI of more than 30)4. Many more are merely overweight.

This isn’t just a rich world problem. While in America some 41% of the population is obese, many other countries exceed this level. 45% of Egyptians are obese; 42% of Saudis are obese, for example5. Compare to current usage levels and it’s clear GLP-1 receptor agonist drug usage clearly has room to grow.

Thus far, the major barriers to GLP-1 receptor agonist adoption have been cost and availability. Both are about to change.

In the USA, the drugs typically cost around USD 1,000 per month6 and insurance doesn’t always cover this cost for obesity. Insurance companies definitely don’t cover the cost for the merely overweight.

In the UK a monthly course of GLP-1 drugs typically cost around £2507. They are available for free on the National Health Service (NHS) for those with a BMI of more than 35 and at least one obesity-related health complication. But the NHS has slowed its roll-out of these drugs among those who are eligible because they are worried that the cost of the drugs and the large number possible users might mean GLP-1s take up around half the entire national budget for all drugs.

However, some studies suggest it only costs around $5 to manufacture a month’s supply8. High prices are sustained because the drugs are protected by patent. But compounded versions of GLP-1 drugs have been allowed for use in the US owing to supply shortages. These compounds can be distributed without regard to patent protection; the American direct to consumer pharmaceutical company HIMs has done exactly that, responding to Ozempic’s supply shortage.

As newer, more effective classes of GLP-1 drugs become available, older versions may also lose some of their pricing power. We’ve already seen this with Liraglutide, which came off-patent in 2024 and is now widely commercially available in the UK and elsewhere. However, as an early-generation GLP-1 drug it requires daily dosing, whereas semaglutide can be taken weekly. liraglutide is also generally less effective for weight loss than semaglutide.

Semaglutide starts to come off patent in many countries from 2026. This means that generic drug manufacturers are preparing today to release cheaper biosimilar versions of Ozempic, further bringing down costs. China should be the first major market where this happens; it also has a high prevalence of obesity and type two diabetes. We are aware of at least 11 semaglutide biosimilars from Chinese companies that are in final stage clinical trials9. If they are shown to be as safe and effective as Ozempic and Wegovy, competition among GLP-1 manufacturers could increase and prices should come down.

4. The Role of Fast Moving Consumer Goods’ Super-Users

At first glance, 5% of any population taking GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs doesn’t seem like a big deal. But this point of view doesn’t account for the role of super-users of fast moving consumer goods (FMCGs).

This is probably easiest to understand with cigarettes.

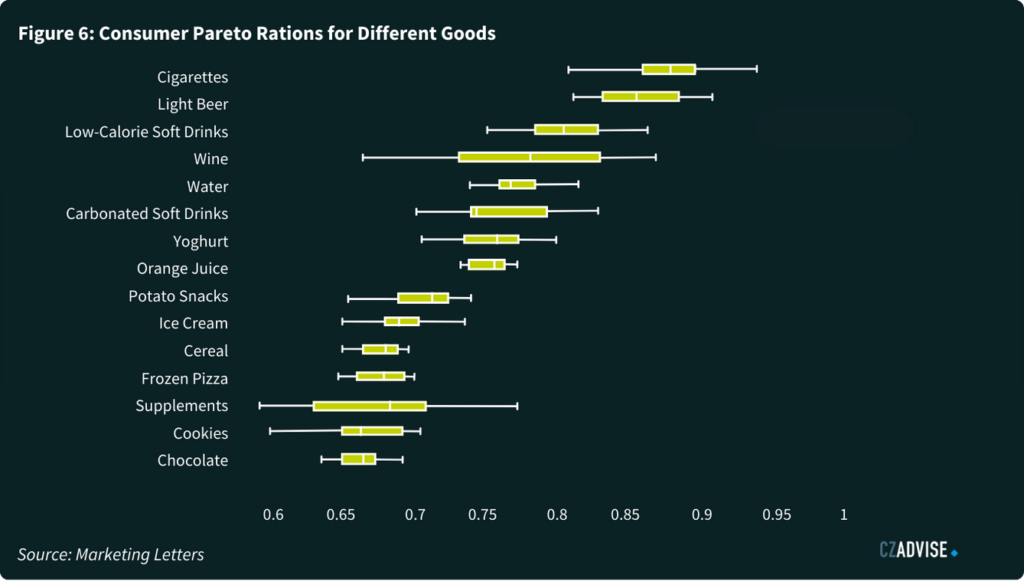

Most people in the UK don’t smoke. They buy zero cigarettes. 12% of adults do smoke, and they account for all cigarette sales. Of those who do smoke, some will only smoke occasionally, and perhaps account for 10 cigarettes a week. But some will also smoke heavily, perhaps 40 a day. The small subset of people who smoke 40 cigarettes a day will account for virtually all cigarette sales.

A less extreme example applies to most FMCGs. Research shows that in the United States of America, the top 20% of users accounted for at least 70% of soda sales10. The top 20% of ice cream users accounted for around 65% of purchases. It’s similar for cookies and chocolate too. This is the FMCG version of the 80/20 rule. In this case, it seems to be the 65/20 rule for processed food and drink.

We can also assume that super-users of soft drinks, ice creams, cookies, chocolate and candy might in many cases be compulsively eating them, and are more likely to be overweight. We’d therefore expect there to be overlap between people who are super-users of FMCG foods and people who are using GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs to manage weight loss. The 5% of people Americans currently on GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs could easily account for more than 5% of American sugar consumption. This is likely to be the case for most other countries too.

Research is emerging that GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs are changing food consumption habits. Much of this information comes from the USA, which is the most developed market for GLP-1 drugs. 70% of Novo Nordisk GLP-1 receptor agonist sales are in the USA. More than 80% of Eli Lilly’s GLP-1 receptor agonist sales are there.

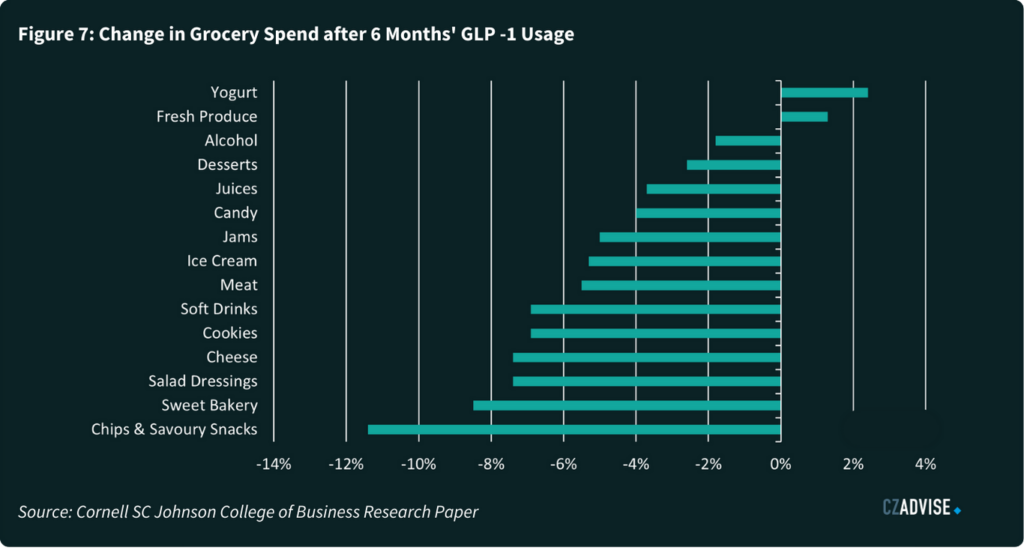

One recent study showed that households with at least one GLP-1 receptor agonist user reduced grocery spending by around 6% in the six months following adoption, with high income households reducing spending by 9%11. The reductions were driven by larger decreases of calorie-dense processed items, while purchases of nutrient-dense products like fresh fruits, vegetables and yogurts grew. Interestingly, the magnitude of reduction decreased after 6 months, though it’s not clear why.

Away from academia, Walmart reported as long ago as October 2023 that they observed changes to consumer buying patterns as a result of GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs12. Walmart are in an interesting position. Their stores sell groceries but also have in-store pharmacies. Many of their customers have loyalty cards which means the company can track their buying habits in real-time. In 2023 they saw signs that customers who bought GLP-1 drugs also bought “slightly less units, slightly less calories”.

5. How GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Might Impact Sugar Consumption

Sugar consumption is notoriously difficult to model and analyse. Most people have no idea how much sugar they eat in the course of a day. Sugar is a useful ingredient that finds its way into many foods. People who keep journals of their food intake tend to underreport consumption. If this is true at an individual level, it’s even more true at a population level. Analysts can access excellent statistics on sugar production and trade, but virtually nothing on sugar stock levels or consumption. Please take the discussion that follows as an illustration, not the precise truth.

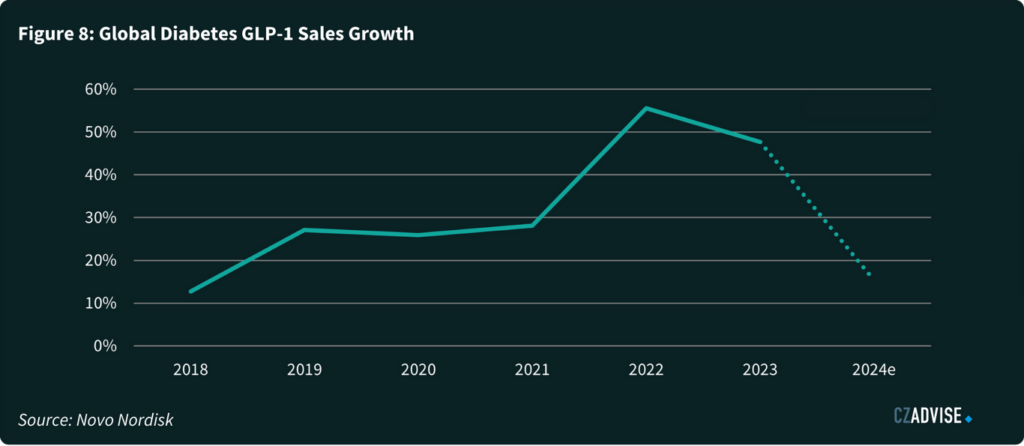

The dominant market for GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs today is the USA. But we are seeing strong growth in Europe, the Middle East and China. GLP-1 receptor agonist sales growth rates are around 50% a year for diabetes treatment, but much higher for the new classes of obesity-optimised GLP-1 receptor agonists. We think this means that GLP-1 receptor agonist drug use could continue to grow in the next 5 years, to a point where we could see at least 5% of the population of most advanced and upper-middle income countries using them routinely.

We’ve modelled what this might mean in the UK as an example.

- There are 69m people in the UK.

- 55m are adults.

- 20% of these adults are obese, or 11m people.

We’ve assumed this is the total UK market for GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs.

We’ve then assumed that 30% of these people will ultimately end up on GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs, or 3.3m people, which is around 5% of the overall population. We’ve also used the 20/65 rule to assume that there are 11m sugar super-users in the UK who account for 65% of sugar sales.

UK sugar consumption today is around 1.72m tonnes a year.

- If we assume adults and children eat the same amount of sugar per person, adults eat 1.376m tonnes of sugar a year.

- Adult sugar super users eat just under 900 thousand tonnes of sugar a year in the UK.

If we assume that all 3.3m GLP-1 receptor agonist users are also sugar super-users, and that being on GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs results in a 30% decrease in sugar intake, this would result in a loss 80 thousand tonnes of sugar consumption in the UK as a result of these drugs. That’s a 5% loss.

We’ve already started tapering our sugar consumption estimates for many countries between now and 2030 as a result.

How To Adapt to The Disruption

There are several ways to adapt to GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs.

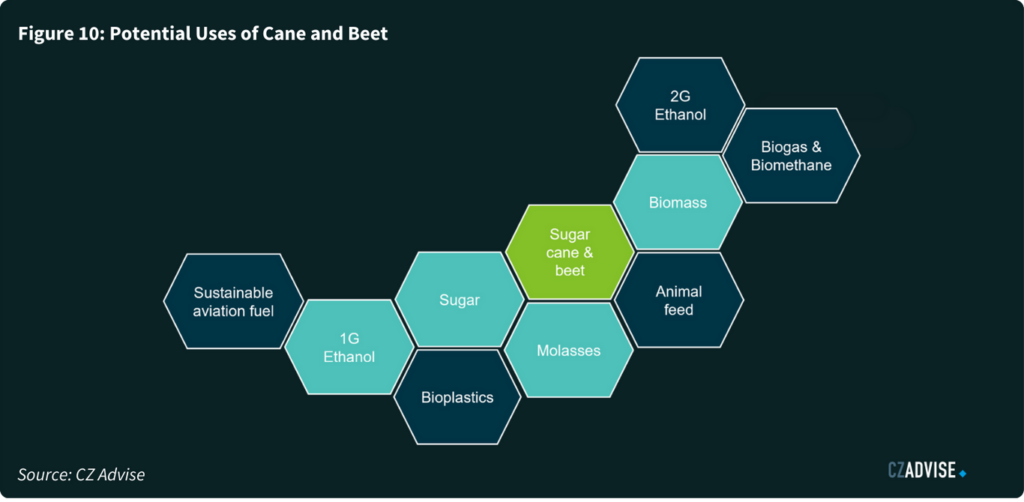

For sugar producers, the adaption can be positive. Sugar is famously “empty calories”, to use a phrase from nutrition. They are pure energy, giving 4 kilocalories for each gram consumed. This is bad news for overweight humans with a sweet tooth. But it’s good news for those trying to find a clean source of renewable energy. Sugar cane and beet are energy crops; it’s just today we mostly use that energy as food energy.

But if consumption of sugar does indeed decline thanks to GLP-1 receptor agonist drugs, the industry can continue to reposition as a clean fuels provider. Already Brazil and India are leaders in using sucrose from sugar cane to make ethanol for use as a road fuel.

But air travel hasn’t decarbonised at all, yet it accounts for at least 2% of global carbon emissions. We haven’t yet got the technology to put batteries into large passenger aircraft. If air travel is to decarbonise in the coming decades, it needs to be through a liquid fuel.

One option is to use a drop-in fuel to replace fossil jet fuel. This sustainable aviation fuel can be made from ethanol via the alcohol to jet process, and by our calculations we’re going to need a lot of ethanol in the coming decades to make this happen. We think there could be demand for as much as 165b litres of ethanol from the aviation sector by 2050. Today the world only makes 112b litres of ethanol each year13.

If you’re a sugar producer and want to learn more about ethanol, sustainable aviation fuel, or even things like bioplastics, and how they can diversify your revenue away from sugar, please contact us.

Stephen Geldart

Head of Analysis

James Brittain

Director, Head of Advisory

Contact us

"*" indicates required fields