August 1, 2024

Introduction

Food security is:

- Growing, making and shipping enough food,

- Making it cheap enough that everyone can buy what they need,

- Ensuring sufficient energy and nutrient intake,

- Ensuring the above three factors are stable through time.

The world’s major food producers, like America, Canada and Brazil, don’t need to worry about growing and making enough food. But they do still need to ensure it gets from farms to cities and is cheap, varied and nutritious. There is no such thing as a country which is entirely food secure.

Indeed, for almost all of human history, the fear of starvation has loomed large. Making food cheap and widely available for 8b people on the planet was one of the 20th century’s crowning achievements. But to keep the status quo is hard work. Countries that aren’t major food producers need to constantly plan in order to ensure their own food security. After all, “each society is only three meals away from chaos”.

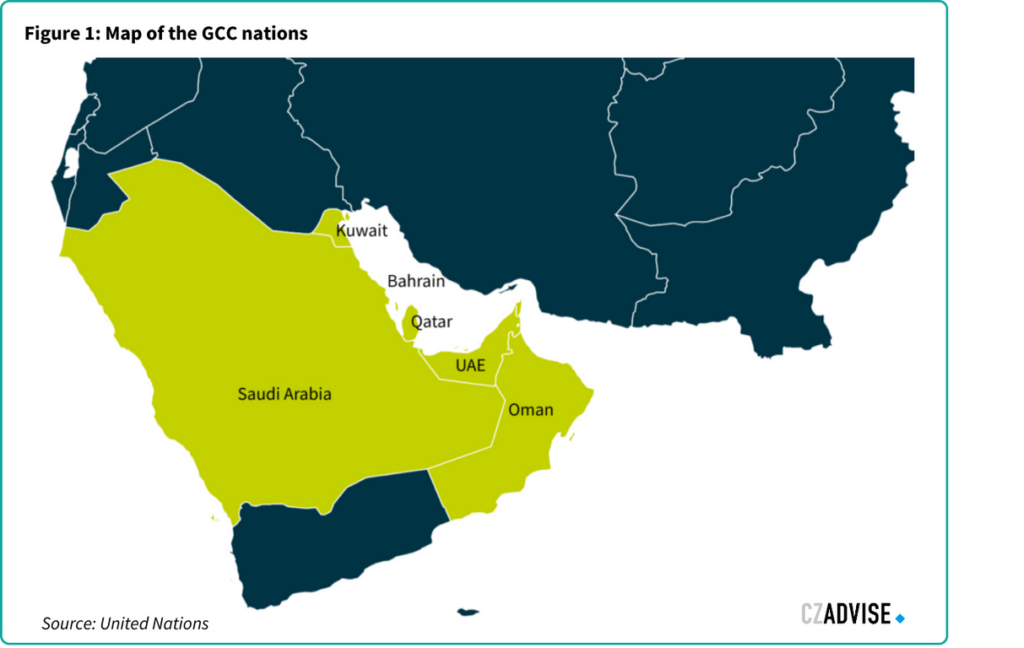

The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) comprises six nations on the Arabian Peninsula:

- Bahrain,

- Kuwait,

- Oman,

- Qatar,

- Saudi Arabia,

- and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

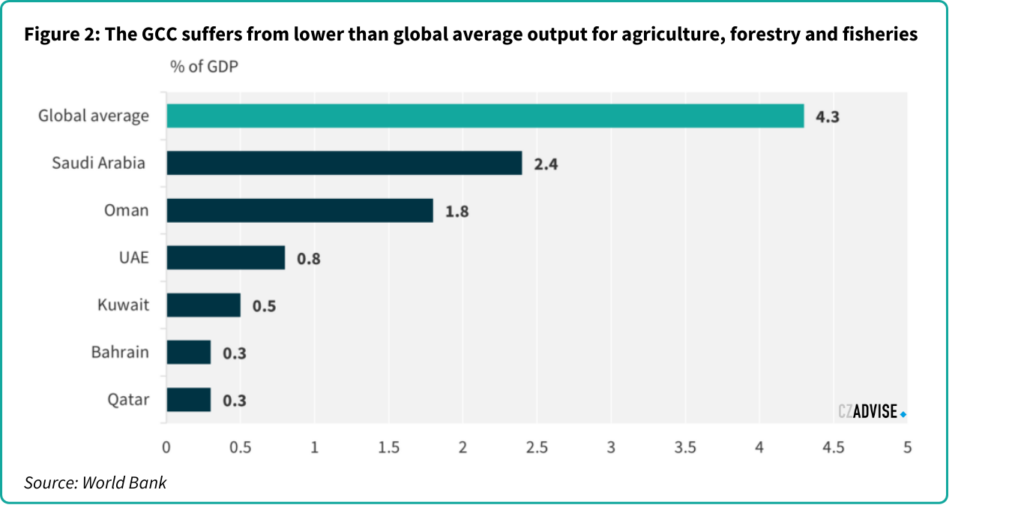

They are not major food producers. The harsh environment of the Arabian Peninsula makes it hard to farm. Renewable freshwater levels are some of the lowest globally and >95% of land on the peninsula suffers from a degree of desertification. High maximum temperatures of 50+ degrees centigrade during the summer greatly limit achievable crop yields and rainfall which is in the range of 50–250 mm per annum is well below that required for industrial crop production.

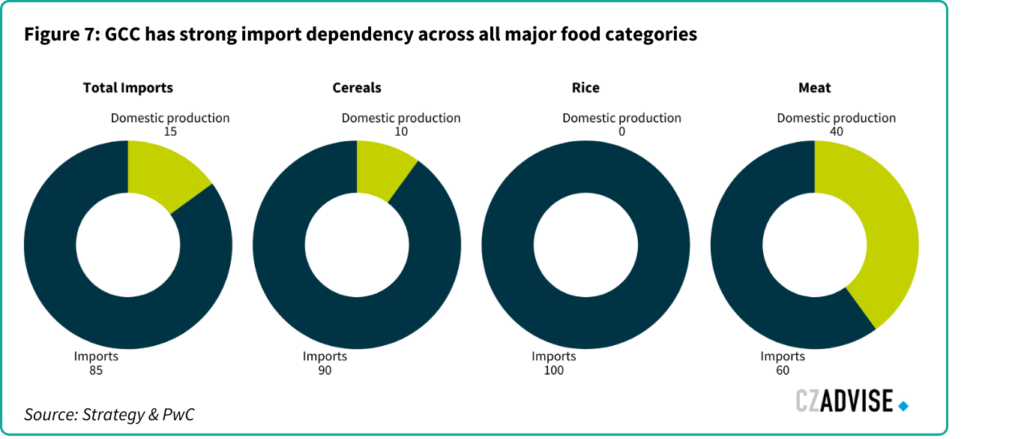

The GCC is therefore one of the most food-import-reliant geographic regions in the world. It only fulfils 15% of food demand from local production. This means that food security cannot be achieved through growing more food. For the GCC, food security is about getting food imports to where they are needed.

In this paper, CZ Advise explores practical solutions the GCC can adopt to maximise food security, with a particular focus on engagement with Brazilian and Southeast Asian exporters.

Food consumption in the GCC

GCC population dynamics

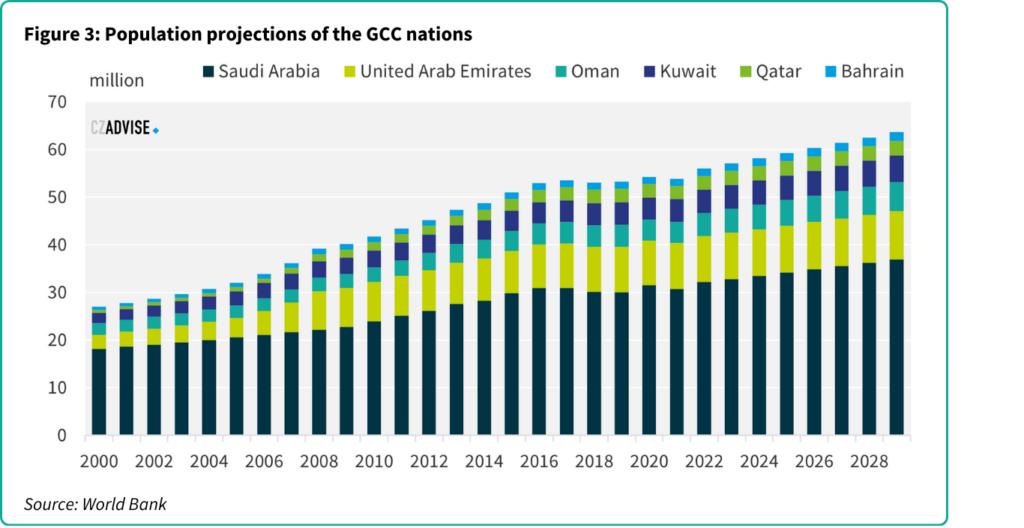

The GCC’s population is growing strongly. At the time of writing, it is home to more than 58m people. The region also has relatively young demographics: more than half the population is under the age of 30.

Expatriates constitute a significant portion of the GCC’s population, particularly in the UAE and Qatar, where expatriates outnumber the local citizens. As the overall population grows, so will the GCC’s food requirements.

Food consumption in the GCC

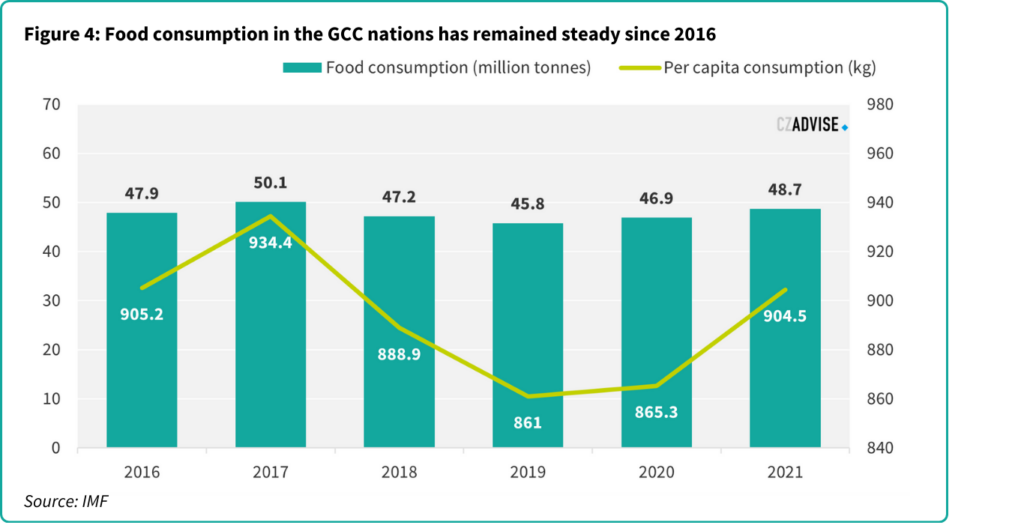

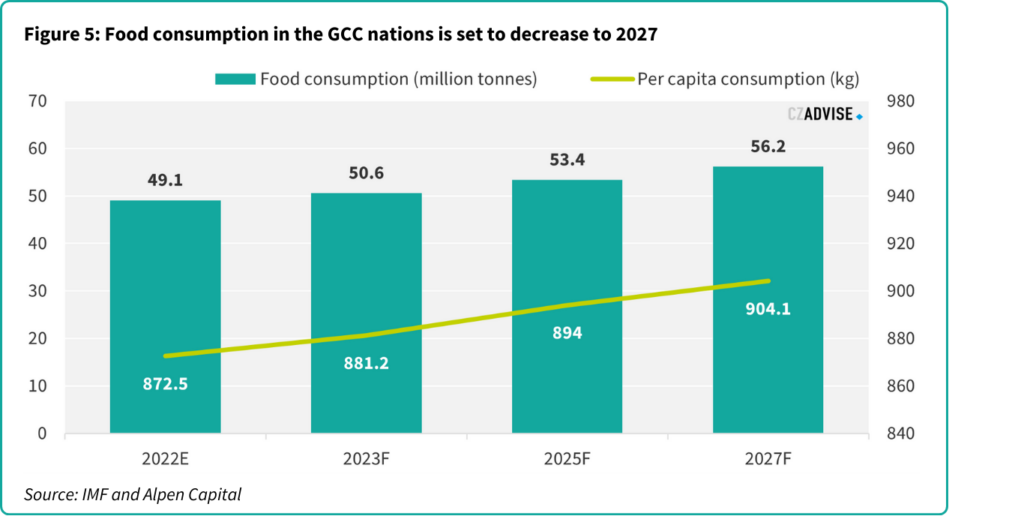

In recent years, per capita food intake in the GCC has been static, at around 900kg per person per year.

Notwithstanding , food consumption in the GCC is expected to grow at a CAGR of 2.8% to reach 56.2 million tonnes by 2027 from the estimated 49.1 million tonnes in 2021 according to the IMF and analysis conducted by Middle East specialist advisory firm, Alpen Capital. This growth in GCC food consumption is expected by the IMF to be driven particularly by Saudi Arabia which under its 2030 economic diversification plan needs to attract millions of more foreign workers for its grand construction projects as well as the further development of its professional services industry.

GCC food consumption trends

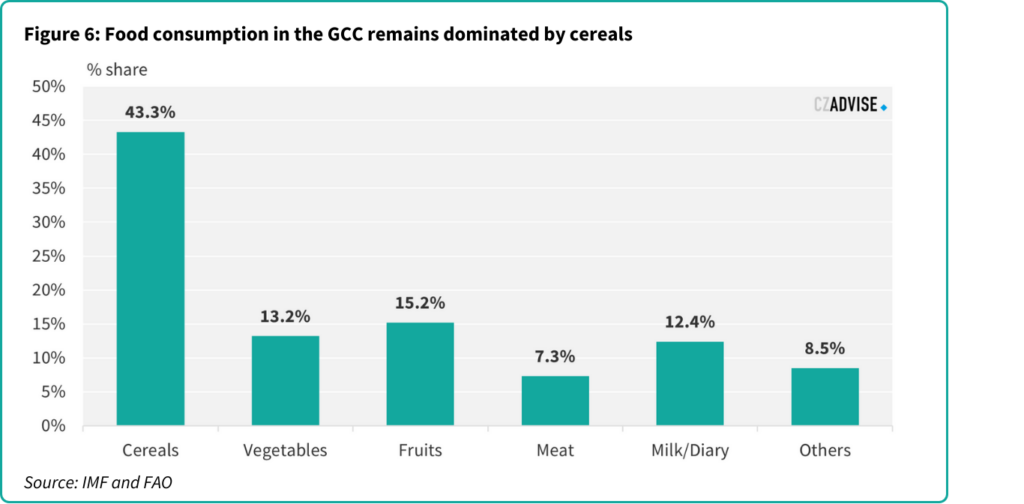

Cereals are the most consumed food category in the GCC nations, though their proportion of total food consumption has decreased from 47.4% in 2016 to 43.3% in 2021. Conversely, other food categories like vegetables, fruits, meats, and dairy products have increased their share of total consumption.

Food security in the GCC

The issue with domestic production

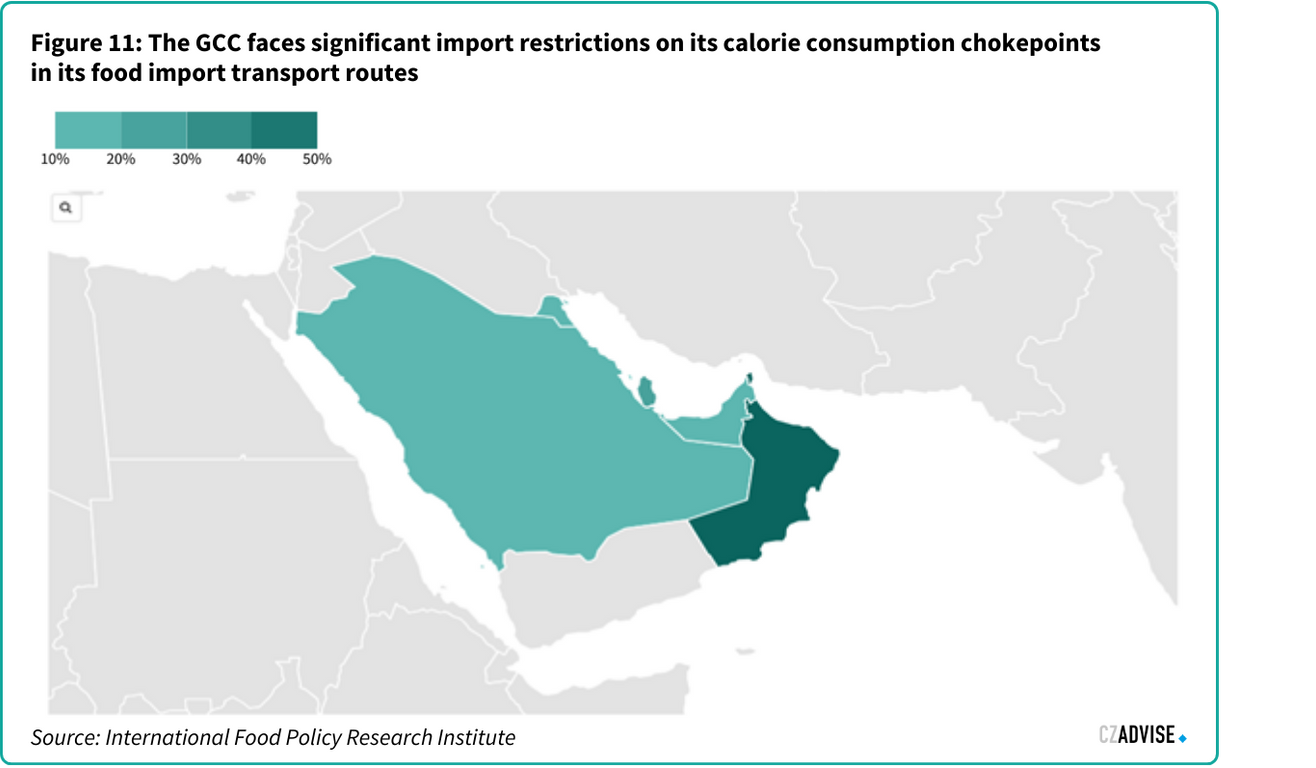

With limited food production potential, the GCC relies on imports. 85% of all foods are imported, but this proportion rises to 90% for cereals. Virtually all rice is imported. This leads to several risks, including supply chain disruptions, price fluctuations, and geopolitical tensions in exporting nations.

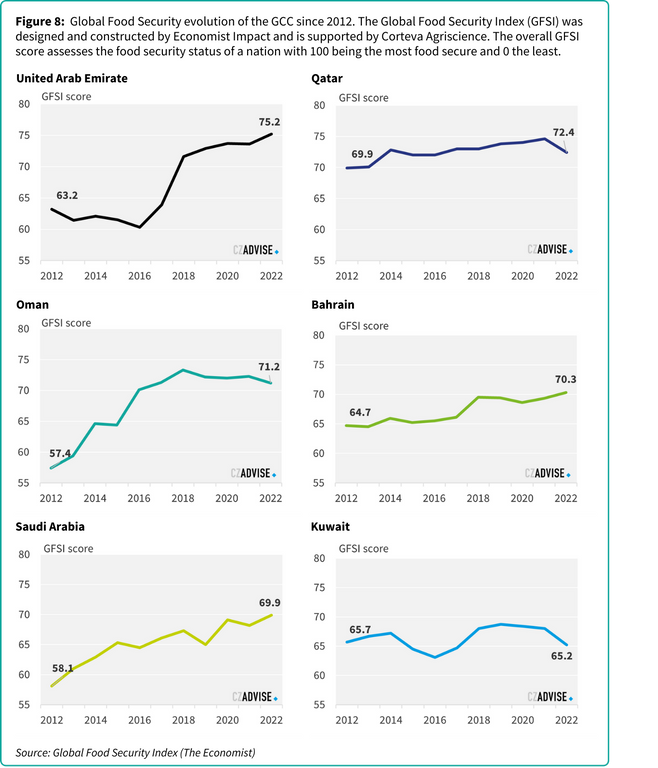

In recent years, the GCC nations have taken strides towards enhancing their food security levels. This progress has been primarily facilitated through a combination of augmenting port operational capacities , bolstering food storage capabilities , and implementing beneficial government subsidies for food enterprises.

This has been particularly the case for the UAE where the government plans to expand the Jebel Ali port to consolidate food imports. The Jebel Ali expansion agri terminal project involves a USD 150 million investment by DP World, in partnership with Adroit Overseas Canada and Al Amir Foods, to develop a complex to store and process essential agricultural commodities. The first phase of this revamped agri terminal is set for completion in early 2025 and is expected to stimulate substantial international trade and enhance bulk handling capacity in Dubai according to the UAE Ministry of Economy. This initiative is part of the UAE’s government aims to boost the contribution of food and agriculture to its economy by USD 10 billion and create 20,000 jobs by 2029.

Spanning nearly 100,000 sqm, the new Jebel Ali agri terminals will be the largest of its kind in Dubai for integrated agricultural processing and silo storage. It will feature a total storage capacity of 200,000 tonnes, developed over two phases, and processing and packaging facilities for up to 500,000 tonnes a year. The terminal is designed to transfer commodities directly from ship to shore through a conveyor belt system.

To further mitigate food security risks, GCC governments have implemented other intervention measures, including financial exemptions and credits to farmers and agri-businesses, mobility exceptions for agricultural workers during lockdowns, and support for packaging and distribution.

Broadly, the two main subsidy schemes are input-based which lowers the purchasing cost of raw materials for farmers, and output-based which pays farmers based on finished agricultural products. For example, Saudi Arabia in 2021 embarked on a large subsidy reallocation program in the poultry sector that aims to lower the level of subsidy on animal feed and instead support finished agricultural products.

Moreover, the UAE has a comprehensive inflation subsidies programme whereby the government pays a monthly subsidy for Emirati families to help them cope with the worldwide rise in fuel, food, electricity and water prices.

These measures have helped preserve short-term food security, preventing some of the extreme situations witnessed in other parts of the world, where countries had to enforce restrictions on food purchases to curb hoarding and panic-buying.

Notably, according to the Global Food Security Index, all GCC nations, except for Kuwait, have significantly improved their food security scores since 2012.

Imports from the immediate region are restrictive

There is a lack of local food imports from the wider Middle East and Africa. Freight methods such as rail and road transport of foods across country borders does not occur at a large scale in the GCC. The GCC Railway, a proposed railway system to connect all six GCC nations, is estimated to cost USD 250 billion according to the GCC secretary and European Union . The project comprises a dual rail line for freight and passenger trains and a 1,190km motorway for cargo trucks. It was scheduled to be completed by 2025, although as of 2023, construction work has yet to start. In April 2023, Iraq also announced a launch date for the multi-billion-dollar rail network project linking its southern Grand Faw Port, estimated to cost more than USD 19.7 billion and to be completed by 2038. Despite these announcements, the projects are long-term commitments and are unlikely to result in immediate improvements in food security transport.

Thus, shipping remains the most important method to transport food products to the GCC. Moreover, as seen below, food insecurity in North and Central Africa remains higher than the GCC, meaning that significant increases in volumes of exports from the immediate neighbouring region is unlikely to happen.

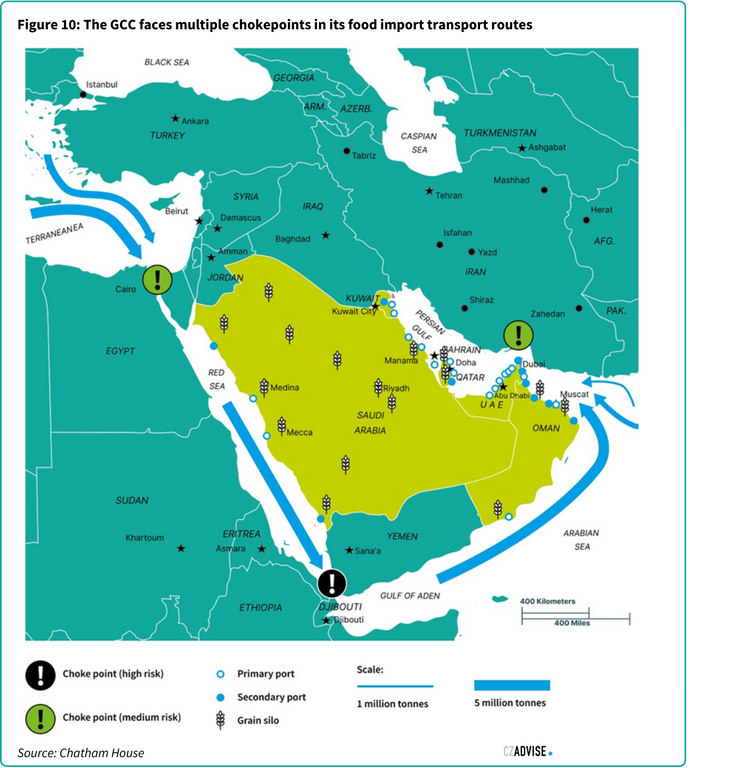

GCC food imports from the wider world means that freight often must pass through three of the world’s most important maritime shipping chokepoints: Bab al-Mandab, Strait of Hormuz and the Suez Canal. GCC importers heavily depend on shipments traveling northward through the Strait of Hormuz and the Strait of Bab al-Mandab. The region’s significant reliance on chokepoints increases its vulnerability.

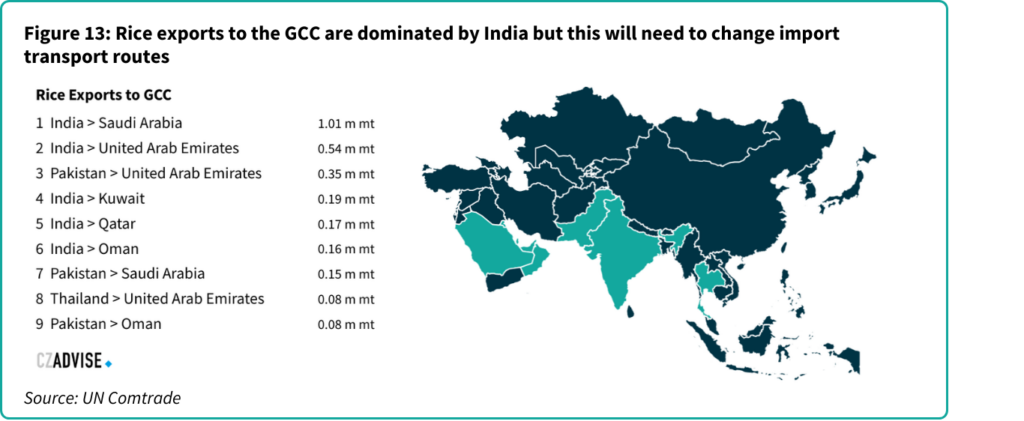

Approximately 39% of the GCC’s wheat and coarse grains imports from the Americas, Europe, and the Black Sea traverse the Bab al-Mandab Strait, while 35% pass through the Strait of Hormuz. Additionally, the latter strait handles 81% of the GCC’s rice imports, predominantly from India.

Recent geopolitical conflict in Israel-Palestine has further exacerbated this issue, particularly in the navigation in the waters near the Bab Al-Mandab which are currently vulnerable to Houthi attacks in Yemen. There are at least 100 confirmed assaults on commercial ships since November 2023.

To tackle these challenges, GCC nations have made significant investments in strategic food reserves. In 2015, Qatar’s Ministry of Commerce and Industry (MoCI) launched the tendering process for strategic silos that aim to increase food security via storage and warehousing capacity addition. A project under this programme, focussing on rice imports comprises 51 concrete storage silos with a total storage capacity of about 300,000 MT. There are two storage warehouses (double and triple module) to store rice with storage capacities of 28,000 tonnes and 44,000 tonnes respectively.

The majority of grain stockpiling facilities in the GCC region are located in Saudi Arabia. These reserves can be tapped into during periods of acute import shortages. Saudi Arabia is the sole GCC member with access to the Red Sea, providing a partial shield against food price volatility caused by increased expenses or shipping interruptions. However, this advantage does not entirely mitigate the impact, as imports must traverse lengthy routes across the country, through desert terrain.

Apart from Oman, which has ports on the Arabian Sea, the remaining GCC nations lack direct access to alternative shipping paths for food imports. Should disruptions or crises in imports result in heightened food prices, multiple policy interventions would be necessary. These might include the release of strategic reserves and reliance on Saudi food re-exports to alleviate prices and uphold consumption levels at relatively stable rates.

Exporting goods from ASEAN countries to the GCC via ship without transiting through the Bab Al Mandab strait offers significant advantages. This route provides a safer and more reliable passage for trade, ensuring smoother logistics operations and minimizing the possibility of delays or damages to the goods in transit. Additionally, by avoiding the Bab Al Mandab strait, ASEAN exporters can optimize their shipping routes, reducing fuel consumption and overall transportation costs, including insurance, which ultimately enhances the competitiveness of their products in the GCC.

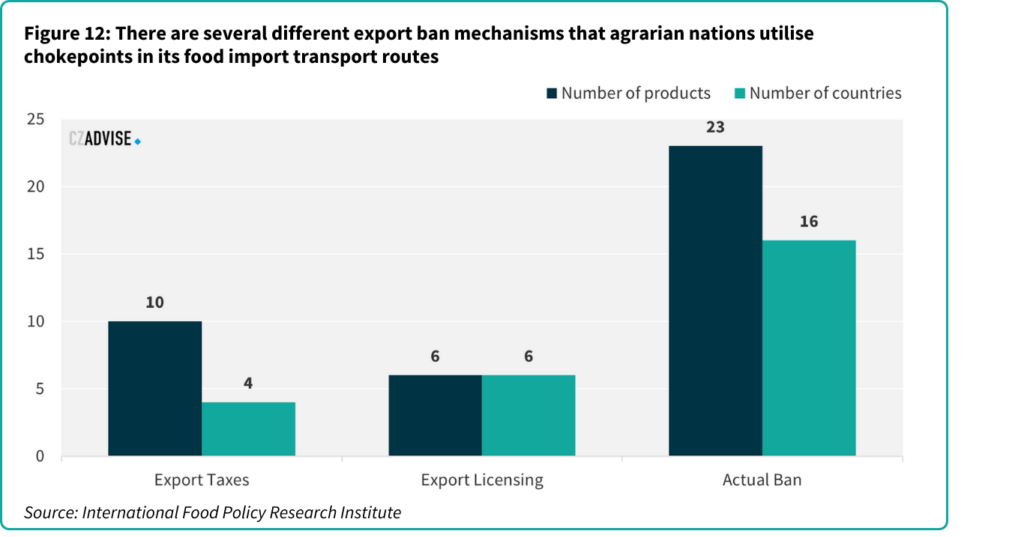

Export bans by GCC exporters

Export bans pose a significant supply risk for food-importing countries. There is a growing trend of national food protectionism, with key food suppliers to the GCC frequently halting exports of essential goods.

In August 2023, the UAE enforced a four-month ban on rice exports and re-exports across all rice varieties, following India’s decision to suspend non-basmati rice exports due to crop damage from heavy monsoon rains. Concerns about future rice supplies are compounded by predictions of a strengthening El Niño, which could affect further affect Indian rice yields.

Export bans not only impact plant-based products but also affect other vital commodities such as live sheep. Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest importer of live sheep, encountered challenges when its primary suppliers, Australia and New Zealand, imposed a ban on live animal exports in April 2023 due to welfare concerns. Consequently, GCC importers find themselves in a precarious position, needing to swiftly identify alternative sources of supply. This task becomes even more daunting if multiple exporters simultaneously restrict shipments. Despite efforts by the G20 to curb the use of export controls, the looming threat of unilateral trade measures persists, presenting a significant risk to the food security of the GCC.

Current active food export restrictions directly affecting GCC nations

| Type of export restrictions | ||

| Actual ban | Country | Food products |

| Algeria | Pasta, wheat derivatives, vegetable oil, sugar | |

| Argentina | Beef meat | |

| India | Broken rice | |

| Non-basmati rice | ||

| Onions | ||

| Sugar | ||

| Wheat | ||

| Wheat flour, semolina, maida | ||

| Kuwait | Chicken meat | |

| Grains, vegetable oil | ||

| Lebanon | Processed fruit & vegetables, milled grain products, sugar, bread | |

| Morocco | Tomatoes, onions, potatoes | |

| Russia | Rice, rice groats | |

| Tunisia | Fruits & vegetables | |

| Export licensing | Argentina | Beef meat |

| India | Wheat flour | |

| Myanmar | Rice | |

| Export taxes | ||

| Argentina | Soybean oil, soybean meal | |

| India | Basmati rice | |

| Onions | ||

| Parboiled rice |

What options does the GCC have to improve food security?

Achieving food security domestic production is improbable for the GCC. Therefore, the GCC countries must undoubtedly continue to rely on diversified global food import strategies to ensure food security.

CZ believes that food imports from Southeast Asia and Brazil can play a crucial role in enhancing food security in the GCC by diversifying the region’s food supply chains.

Southeast Asia is a significant producer of various agricultural products such as rice, fruits, vegetables, and seafood. The proximity of Southeast Asia to the GCC, coupled with established trade routes, allows for timely and cost-effective transportation of fresh and processed food products.

Brazil, as one of the world’s largest agricultural exporters, is another vital partner. Brazil’s vast and productive farmlands yield substantial quantities of grains, meat, poultry, and sugar. Investments in Brazilian agribusiness and port infrastructure by GCC owned enterprises, such as DP World’s investments in Santos’ port infrastructure, further strengthen these trade ties.

Tapping into Southeast Asia

Over reliance on single food partners

A common challenge faced by GCC nations is their heavy reliance on specific countries for a large portion of their staple goods. Typically, rice imports into the GCC were heavily reliant on Indian exporters, accounting for more than 80% of total volume. However, in 2023 India banned rice exports following a poor crop, highlighting the GCC’s vulnerability.

There are however other major rice producing nations that could fill the gap caused by the India export ban. In Southeast Asia both Thailand and Vietnam are large rice exporters with 8.5 and 7.9 million tonnes respectively per year.

As well as ensuring volume security, by expanding their sources of imports across various regions and suppliers, the GCC can mitigate the risks associated with uncompetitive pricing. Consequently, importers and consumers can benefit from more stable and predictable pricing, as well as a broader array of options. This is especially important for rice given the large price increases exhibited over the past 12-month period.

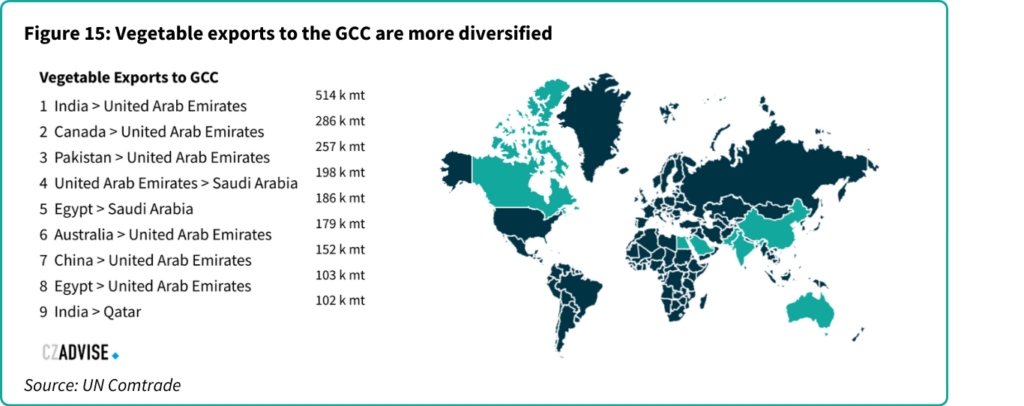

As mentioned previously, there has been an increasing shift in fruit and vegetable consumption in the GCC. This aligns directly with import opportunities from Southeast Asia. Given that ASEAN is known for its production of fresh vegetables, soybeans and tropical fruits, among others, the GCC could explore a wider variety of agricultural products to import. As shown below, vegetable imports are more diversified, sourced from a wider range of countries. This is a good example of how GCC can mitigate their food security risks. However, no Southeast Asian nation makes up the top exporting nations.

The potential of Southeast Asia

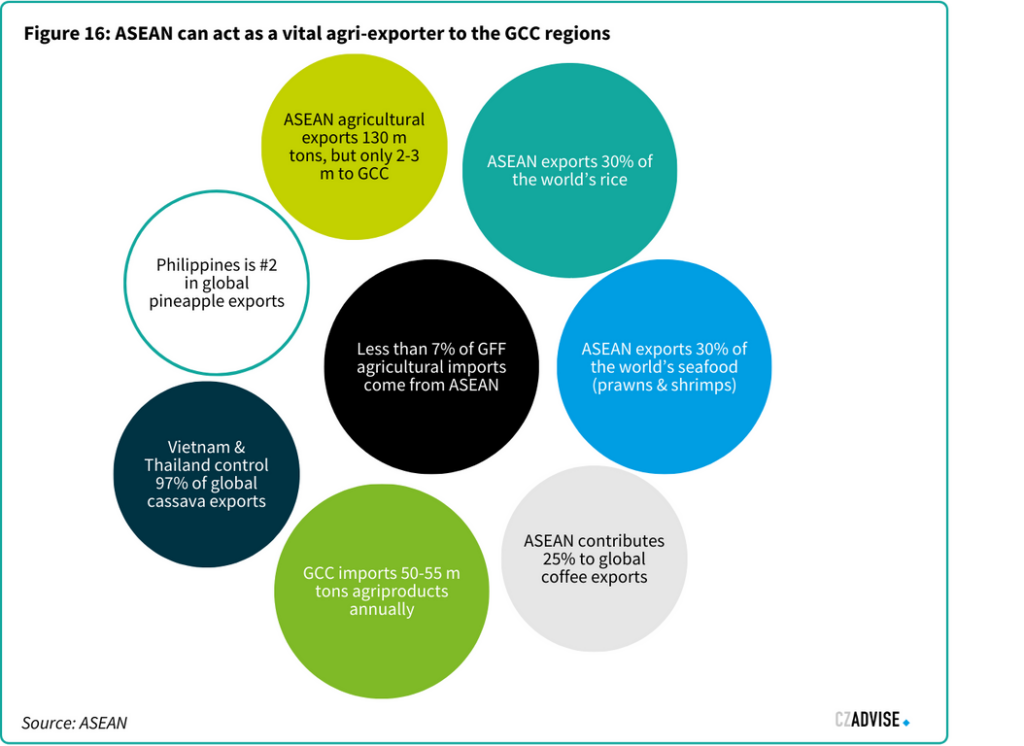

Despite serving as a significant hub for food production and export, the GCC has limited agri-trading with the Southeast Asian ASEAN bloc. Less than 7% of the agricultural goods imported by the GCC originate from ASEAN.

This is despite ASEAN boasting abundant agricultural output, including rice, corn, sugarcane, cassava, soybeans, tropical fruits like pineapples and lychees, bananas, palm oil, seafood, and coffee. Among the top ten rice-producing nations globally, ASEAN countries hold a significant position, with their contribution constituting around 30% of the global total.

The GCC annually imports between 50 and 55 million tonnes of agricultural commodities per year. Even though ASEAN countries export approximately 130 million tonnes of agricultural commodities, they only export between 2 – 3 million tonnes to the GCC, despite their closer geographic proximity compared to other major GCC agricultural exporters and avoidance of maritime chokepoints as previously mentioned. A main reason for these lower export volumes is due to the demand and closer geographic locality of the massive Chinese market to the ASEAN bloc. This is compounded by the ASEAN–China Free Trade Area (ACFTA) which is a free-trade area among the ten member states of ASEAN and the People’s Republic of China. This ensures tariff free food exports and imports to the members of the free trade agreement.

Across ASEAN, agricultural exports have been steadily increasing, driven by enhanced productivity, trade liberalization, and rising demand from a growing and wealthier regional consumer base. In 2022, agricultural products constituted ~55% of ASEAN’s total exports.

Beyond the existing trade and investment landscape, several strategic opportunities for closer collaboration between ASEAN and GCC exist. Strengthening supply chain connections could facilitate increased imports, addressing food security challenges for the GCC.

The investment in upgrading port facilities globally has been a trademark feature of GCC owned port companies such as DP World. However, investments in ASEAN port infrastructure remain extremely limited compared to the other investments that have occurred in localities such as Brazil. DP World’s investment in ASEAN ports is highly viable, as it would streamline the trade flow of key exports such as rice to the GCC nations. This is particularly important as Thailand exports continue to increase throughout the following years given the export bans active in India.

Another avenue for collaboration lies in the integration of halal food value between the two regions. While currently a niche sector, significant ASEAN markets like Indonesia and Malaysia have the potential to supply halal products, including food, to GCC countries. Standardising halal certification processes and training halal auditors could unlock economic benefits in this sector.

Bilateral relations between ASEAN and the GCC

Trade relations between ASEAN and the GCC have shown promising signs of development in recent years. In October 2023, the first ASEAN-GCC Summit took place in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia marking the start of a new formal cooperation mechanism which could lead to consensus building and new trading arrangements.

Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim has also called for negotiations to start on a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between the two blocs. The two trade blocs have agreed to identify cooperation in the development of sustainable and circular agriculture and in the promotion of sustainable food production and promote trade and investment opportunities in food and agri-based industries and encourage exchange of information, sharing of experiences, research, modern technologies and best practices, as well as through conducting capacity building activities in areas such as food and halal industry development, including various standards for halal food certification. Leaders of the GCC and ASEAN have agreed to hold the ASEAN-GCC summit every two years with the next summit set to take place in Malaysia in 2025.

There are several possibilities and incentives for GCC investment in Thailand specifically:

- BOI Incentives: The Thailand Board of Investment (BOI) offers incentives such as tax holidays, exemptions, and deductions to foreign investors, particularly in infrastructure projects.

- Special Economic Zones (SEZs): Investments in SEZs can provide additional benefits, including simplified customs procedures and additional tax incentives.

- Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs): Thailand encourages PPPs for large infrastructure projects, offering opportunities for GCC investors to partner with Thai companies and government entities.

- Technology and Expertise: GCC nations, particularly the UAE through companies like DP World, have significant expertise in port management and logistics, which can be leveraged to modernize Thai ports.

Expanding investments in Brazil

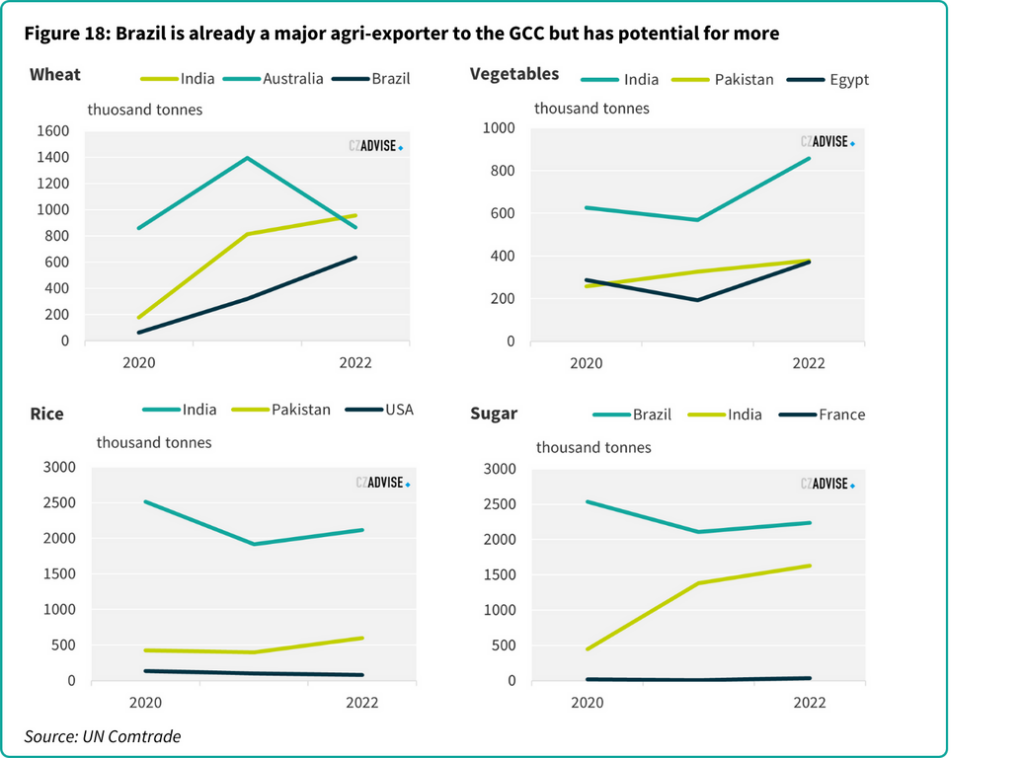

Brazil is a pivotal agricultural export partner for the GCC countries, particularly in the supply of sugar, wheat, and meat, where it ranks among the top five exporters. Brazil’s extensive and efficient agricultural sector allows it to produce large quantities of these commodities, ensuring a reliable supply to the GCC.

Brazil’s agricultural exports are crucial in ensuring food security. Moreover, Brazil’s expertise in agribusiness and its advanced agricultural technology provides an additional layer of reliability and efficiency in the trade partnership.

GCC land purchasing in Brazil

GCC sovereign wealth funds can bolster the region’s food security by investing in agricultural land abroad. By investing in agricultural lands, these funds can boost crop yields and help ensure a stable and consistent supply of essential food commodities.

Although it is possible for foreign companies to purchase agricultural land in Brazil, there are specific and stringent regulations and restrictions in place. Brazil’s legal framework for foreign land ownership aims to balance economic interests with national security and sovereignty concerns.

Since 1971, the Brazilian government has imposed restrictions on the outright purchase of rural farmland by foreigners or foreign-based companies for food security reasons.

According to the law, foreigners are allowed to own no more than one-fourth of any given municipality, and no single nationality can hold more than 10% of the land in that area. Current legislation permits foreigners to purchase up to 50 agricultural modules, which vary in size from 250 to 5,000 hectares depending on the region and soil productivity. Below is a summary of the main mechanisms of restriction.

- Restrictions on Land Size: Foreigners and foreign-controlled companies can purchase land, but there are limits on the size of the land they can acquire. The restrictions vary depending on the location and the total area of the municipality where the land is located. Generally, the purchase of large tracts of land is subject to more stringent controls.

- Approval Requirements: Larger acquisitions typically require approval from Brazilian government authorities. This may involve various agencies, including the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA), which oversees land use and agricultural policies.

- Strategic Areas: There are additional restrictions on foreign ownership in areas considered strategically important for national security, such as border regions or areas near significant natural resources. In these cases, purchases may be prohibited or subject to stricter scrutiny and approvals.

- Legal Entities: Foreign companies that wish to purchase agricultural land must establish a Brazilian legal entity to do so. This entity is subject to Brazilian laws and regulations, including those governing foreign investments and land ownership.

- Legislative Changes: The legal framework governing foreign ownership of agricultural land in Brazil has been subject to changes and debates over the years. Various legislative proposals have been introduced to either ease or tighten restrictions, reflecting the ongoing national discourse on balancing foreign investment with sovereignty and security concerns.

- As such there have been limited land investments made by GCC nations with only the Qatar Investment Authority having made in roads with a large-scale asset purchasing in Brazil. These have however been through asset purchases which support a significant proportion of farming land.

Investing in Brazilian food processing companies

Despite the restrictions on land purchasing agreements, GCC have expanded their reach into Brazil’s food and beverage sector via share purchasing and joint ventures.

Investing in Brazilian food processing companies ensures a reliable and high-quality supply of essential food products tailored to the region’s needs. By controlling the processing stage, GCC countries can guarantee that imported foods meet their safety and quality standards, while also benefiting from value-added products with longer shelf lives. This strategic investment reduces dependency on raw commodities, stabilizes prices, and mitigates risks associated with supply chain disruptions.

Technology and expertise transfer in food processing from Brazilian companies to the GCC can also significantly enhance the region’s food security by enabling local production of high-quality, value-added food products. In 2023, Brazilian food processor BRF agreed to form a Saudi joint venture with Halal Products Development Company (HPDC), in a bid to develop the halal meat industry in Saudi Arabia.

BRF, which owns up to 70% of the joint venture, said the new company will have a combined investment of $500 million. The venture will operate in the entire chicken production chain in Saudi Arabia and sell fresh, frozen and processed products. HPDC is a subsidiary of Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF).

In 2016, PIF subsidiary the Saudi Agricultural and Livestock Investment Co. (SALIC), a fully owned subsidiary of the Public Investment Fund, also entered a share partnership in 2016 with Minerva Foods, a Brazilian red meat producer. In 2020, SALIC raised its stake in Minerva Foods, from 26 to 34 percent.

Investing in Brazilian infrastructure and logistics

An example of capital investments by GCC based companies includes DP World, a Dubai based government owned logistics and ports operator, that has made significant investments in Brazil’s port infrastructure.

DP World is investing in port infrastructure in Santos, Brazil, to enhance its global logistics network, specifically targeting the efficient and reliable transportation of agricultural products. Santos, being the largest port in Latin America, is crucial for facilitating Brazil’s significant exports of grains, meat, and other food products. By improving this port’s capabilities, DP World aims to ensure smoother and more cost-effective trade routes, which directly supports the food supply chains essential for regions highly dependent on food imports, such as the GCC.

DP World’s investment includes USD 85 million to boost container capacity in Brazil in 2023 and 2024 via their Brazilian subsidiary DP World Santos. The investment is destined for the acquisition of new port equipment for its terminal located on the left bank of the Port of Santos, Brazil.

The investment also includes the USD 35 million for an extension of the dock by an additional 190 meters announced in 2023. Scheduled for completion in late 2024, DP World’s terminal will be able to berth two Q-max scale (345+ meter) vessels, creating significant opportunities to boost carrier efficiency. The new equipment also allows the terminal to expand capacity to 1.7 million TEUs. Ultimately, these investments indirectly support the food and beverage sector by facilitating the export of Brazilian agricultural products to the GCC region and beyond.

Moreover, in 2024 DP World joined forces with Brazilian railway operator Rumo to build a new terminal at the Port of Santos, to handle 12.5 million tonnes a year of grains and fertilizers. Bilateral relationships between GCC and Brazil.

GCC and Brazil bilateral relations

In the early 2000s, ties between the GCC and Brazil were revitalized as both regions showed a renewed commitment to strengthening relations through political exchanges and bilateral initiatives. Although Brazil had initiated contacts with the UAE and Qatar in the 1990s, a systematic effort to enhance these ties only gained momentum in 2000. This effort included Brazil establishing a commercial mission in Dubai in 2002 and beginning agreements across various economic sectors. The inaugural Summit of South American-Arab Countries (ASPA), convened by Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva in 2005, played a pivotal role in bolstering relationships between Latin America and the Gulf. This increased Brazil’s significance in the Arab Gulf, culminating in the signing of an Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement between the GCC and MERCOSUR. Talks for a free trade zone began in 2006 but have yet to be concluded. Following the first ASPA summit in 2005, three additional summits were held: on 31 March 2009 in Doha, Qatar; on 1–2 October 2012 in Lima, Peru; and on 10–11 November 2015 in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

How can CZ help improve GCC food security?

CZ has strong expertise in ASEAN, Brazil and GCC geographies. We have heavy local presences in Southeast Asia with offices in four of the ten ASEAN nations, notably Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam and the Philippines. Furthermore, CZ has local GCC presence in Dubai, UAE as well as an office in Sao Paulo, Brazil giving the company a deep understanding of trade between these three blocs.

Corporate advisers in agricultural and food production

CZ Advise can provide tailored corporate finance assistance in agri-business, bioenergy and food supply chains. CZ Advise is the largest agri-focused financial advisor in Brazil and South East Asia and has advised on more than USD 5.4bn debt & equity transactions.

For more information, please contact Luis Felipe Trindade in Brazil or Stefano La Valle in Thailand.

Luis Felipe Trindade

Associate Director, Global Head of Corporate Finance

Stefano La Valle

Head of Corporate Finance Asia

Food Sourcing Optimisation and Stock Management

Food sourcing requires a deep understanding of markets, price movements, suppliers and international supply chains. CZ Advise’s analysis and consulting teams can advise on risk management, partnerships and investments overseas.

CZ’s physical trading teams can also assist with food procurement, shipment and stock management. As well as ensuring continued prompt supply and storage of foods, we can also provide stock visibility as part of our service, increasing transparency in the food supply chain.

James Brittain

Director

Price Risk Management

CZ works with thousands of food producers and buyers globally on their long-term hedging programme, managing price risk by locking in affordable hedge levels far in advance of shipment when the futures market presents such opportunities.

CZ can support existing in-house price risk management expertise, enabling predictable pricing and budgeting. CZ embeds hedging within a physical contract, taking responsibility for all margin financing and associated engagement with the futures exchange.

Stephen Geldart

Associate Director, Head of Analysis

Government Relations Support

One of the primary risks to continuity of supply is a failure to secure export allocations and permits at times of lower domestic supply. Key to overcoming this will be ongoing and successful dialogue with relevant government authorities, making the case for a predictable export programme, ideally linked to the actual food producers.

CZ has long assisted food producers and associations in their discussions with government authorities, furnishing them with the required data to engage in a proactive and convincing manner.

Get in touch with us to schedule a consultation.